The gallery dedicated to the Silesian art from the 16th-19th century presents an extensive selection of artefacts originating from that period. A few hundred examples of Silesian painting, sculpture and artistic craftsmanship can be admired in chronological and thematic order. Particularly noteworthy are the sets of the 16th and 17th century painted epitaphs – Renaissance, Mannerist and Baroque, religious sculpture and the pictures by the most distinguished painter of the Silesian Baroque, Michael Leopold Willmann. The display along the gallery corridors features also the artefacts of historical artistic craftsmanship (weaponry, goldsmithery, Silesian stoneware, faience, porcelain, glassware and gobelins).

Renaissance painting is represented by an impressive epitaph for Nicolaus Jenkwitz, originally placed in the church of St Elizabeth in Wrocław. It was painted around 1537 to commemorate the councilor from Wrocław and his family. In its centre, God is depicted as a very old man who holds a huge earthly globe with the Garden of Eden marked on its front. Underneath the unnamed artist painted the figures of the deceased: Nicolaus Jenkwitz, his three wives and their children. All of them kneel and trustingly look upwards in the anticipation of the Redemption. The unknown artist from Wrocław used as his model the print by Lucas Cranach the Elder, published just three years before the Wrocław epitaph in the first complete edition of Luther’s Bible (1534).

A true masterpiece of the painting in the style of Northern Mannerism is The Baptism of Christ painted in 1603 by Bartholomeus Spranger (1546–1611) from Antwerp. It was intended as the centerpiece of the epitaph for Eve and Simon Hanniwaldt in the Holy Trinity church in Żórawina near Wrocław. The painter, an excellent artist who was at that time engaged at the court of Emperor Rudolph II Habsburg in Prague, showed the figure of Christ in a way characteristic for Mannerism. The body is twisted into an almost unnatural pose, figura serpentinata. The refined colours of the picture range through the shades of malachite green and grey, while the expressive play of shadow and light contributes to the Mannerist feel of that masterpiece.

Another valuable painting in the exhibition is an excellent male portrait painted in 1628 by Bartholomeus Strobel (1591–c.1647), of the prominent Wrocław patrician Johann Vogt. A mature man with a moustache and characteristic pointy beard gazes inquisitively at the viewer from the dark background, the canvas reveals just his torso and the coat of arms placed by the painter in the top right corner. The man’s black clothing provides contrast for the white lace-edged collar framing his face.

The realistically painted face of the model reminds many visitors of the contemporary American film star Robert de Niro. Indeed, the resemblance is striking, albeit completely accidental.

The paintings by Michael Leopold Willmann (1630–1706), the most distinguished Baroque painter who worked in Silesia, can be viewed in a few of these rooms. The artist was born in Królewiec [Konigsberg], in his youth made some study trips to Holland (while in Amsterdam he even visited the studio of Rembrandt himself), Gdańsk, Berlin and Prague, and later settled in Silesia. He spent there the rest of his life, painting mostly religious pictures commissioned by the abbots of the Cistercian monasteries in Lubiąż and Krzeszów. The National Museum in Wrocław has in its collection a few dozen of his works, only some of which are on permanent display, among them Orpheus among Animals (c.1670), which together with The Rape of Persephone (c. 1665) represents mythological subjects. The centre of the first composition features Orpheus with his harp – the mythical poet, singer and musician who with his art enchanted people and even Nature itself. Animals are gathered around him: a deer, a dog, a monkey, a leopard, hares, a turkey, peacocks and magpies to represent all the continents known at that time. In this way Willmann showed the universal role of music as the art accessible to all creatures. His other paintings such as The Last Supper (1661) and The Coronation of Mary (1656), Paradise (c. 1670) and Escape to Egypt (c. 1685) are also worth seeing.

Besides paintings, the exhibition contains many excellent examples of Baroque sculpture which once adorned churches in Wrocław and in Lower Silesia. For example the sculptural group The Annunciation by Franz Joseph Mangoldt (d. after 1761). This Moravian artist arrived in Silesia from Brno around 1720 and in Wrocław mostly worked on various commissions from the Jesuits. He made for them two monumental statues of the emperors: Leopold I, the founder of the local university, and his sons Joseph I and Charles VI. Nowadays all three can be admired in Leopoldine Hall – the main hall in the University of Wrocław. The Annunciation, created around 1735, was initially a part of the side altar in the Baroque-styled interior of the Gothic church of the Holy Virgin Mary on Piasek, which was actually completely destroyed during the siege of Wrocław in 1945. The sculptures by Mangoldt are distinct because of their dynamism and the noticeable theatricality of gestures typical for Baroque theatrum sacrum.

Another noteworthy example of Silesian Baroque sculpture is the statue dated 1724, by David Johann Georg Urbansky (c.1675– after 1730), the talented artist who studied in Prague in the workshop of the prominent Bohemian sculptor Johann Brokof. Originally his statue of David (just as the one of Asaf, by the same artist, on display next to him) was the finial of the great case of the pipe organ in the church of St Mary Madgalene. David – a Jewish king and a virtuoso harp player, traditionally thought to be the author of the Book of Psalms – frequently served as a subject for artists from different periods, including the greatest of them: Donatello, Michelangelo and Gian Lorenzo Bernini. The sculpture made by Urbansky demonstrates very good anatomical modelling and a certain monumentality, partly diffused by its very light colour.

The next room is dedicated entirely to Baroque Silesian sculpture. The sumptuous figures of Saints: Barbara, Hedwig and Christina, as well as those of the apostles Andrew and Bartholomew come from the lost main altar (1704–1705) in the Holy Cross church on the island of Ostrów Tumski. Their author was a Norwegian sculptor, Thomas Weissfeldt (c. 1670–1721). Among all of those figures the most expressive is that of St Bartholomew, who was skinned alive, shown holding his own skin in his hands. This scene, full of suffering and exceeding the human capacity for pain, is a truly Baroque vision of martyrdom still terrifying for the viewers.

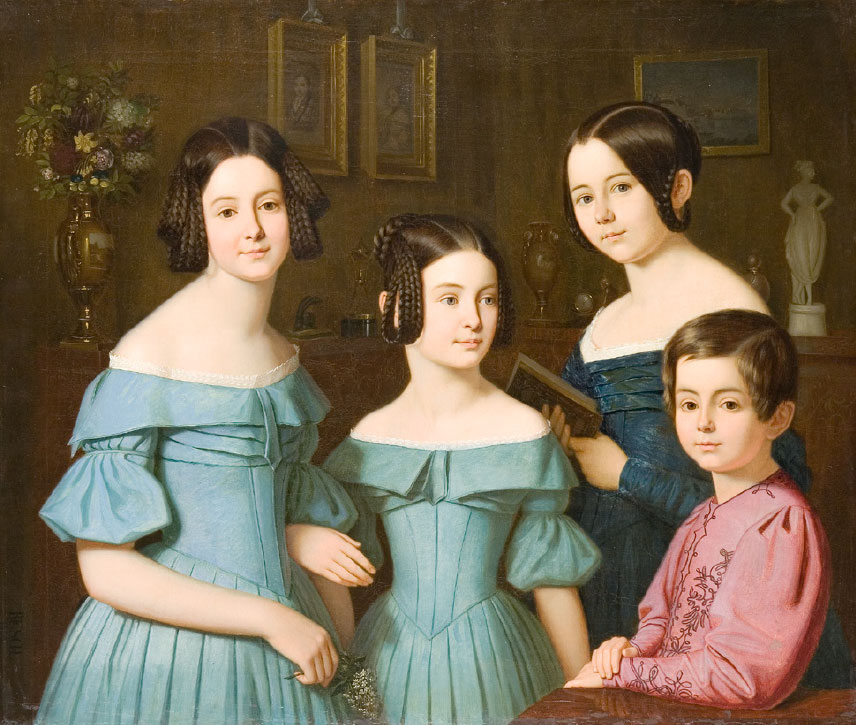

In other rooms the visitors can admire Silesian paintings from the first half of the 20th century such as the work of Ernst Resch (1807–1864), an artist representing ‘bourgeois realism’ of the first half of the 19th century, or Biedermeier, a trend in art associated with the bourgeoisie and addressed to that social class. A small intimate Portrait of children by Resch (1839) features three little girls and an even younger boy. The artist painted all the clothes and intricate hairstyles of the girls with great precision and extreme attention to detail. Their silhouettes are clearly outlined against the dark background of an opulent middle-class home. Further into the background there are shadowy shapes of some decorative objects (among them flower vases, a white porcelain figurine, a clock) and three pictures on the wall: a landscape (?) and two portraits (a man and a woman), most likely the children’s parents.