The Polish contemporary art collection of the National Museum in Wrocław is one of the most interesting and most valuable in Poland. It numbers over 20,000 artefacts spanning such artistic disciplines as painting, print, drawing, sculpture, glass, ceramics and photography, as well as the environment and conceptual works, documentation of happenings and video art.

The exhibition in the Four Domes Pavilion is divided in two: the east wing and the internal courtyard provide the setting for the “Collection of Polish art from the second half of the 20th and early 21st century”, while the west wing holds temporary exhibitions. The entrance hall under the south dome provides the visitors with access to eight multi-media panels, and the possibility of finding out the essential information about the building, the collection, the artists, the museum itself and the educational opportunities on offer.

The exhibits have been arranged in a chronological and thematic order. Viewing is further aided by the system of information sheets describing individual parts of the exhibition which the visitors can find in the boxes conveniently placed in all the rooms. Attractive binders for the collected notes can be found in the museum bookshop located in the west wing.

The starting point for viewing the exhibition is the work of the most prominent between-the-wars painters: Leon Chwistek, Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz and Władysław Strzemiński, who anticipated the contemporary Polish art form, and whose work and artistic theories (‘strefizm’, pure form, unism) exercised a significant influence on the whole 20th century Polish art scene.

The eldest of them, Leon Chwistek, was a co-founder of the Formists and the author of the concept of paintings divided into zones [Pol.’strefy’], dominated by one colour and one multiplied shape). In Portrait of Władysław Leopold Jaworski (1925) and Portrait of the wife (c. 1927) he applied that principle to build a composition.

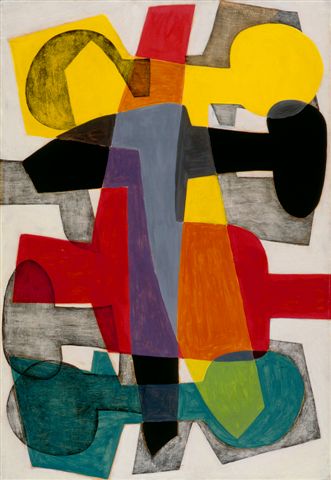

The next part is dedicated to the First Exhibition of Modern Art, which opened in 1948 in Kraków. This was one of the most important artistic events in post-war Poland. The nationwide exhibition, prepared by the Artists’ Club led by Tadeusz Kantor and Mieczysław Porębski, presented work mostly classifiable as abstract and surrealistic, influenced by the tradition of the pre-war avant-garde and the latest artistic trends from Western Europe.

The Pavilion display contains a few of the pieces exhibited at that time, among them those by Maria Jarema, Tadeusz Kantor, Tadeusz Brzozowski and Marian Szulc, united in their search for new forms of expression which aimed at the synthesis of shape, and above all, belief in the new language of art, while their work combined the play of metaphorical spaces and the Surrealist atmosphere.

The aim of the First Exhibition of Modern Art was to create a dialogue with the new audience. It showed a decidedly experimental approach to the design of spatial forms and used kinetic and sound effects inspired by modern technology. Apart from paintings it also included drawings, prints, photomontages, mobile installations and spatial models. In the background, loudspeakers transmitted jazz music, news and statements made by the artists.

These ‘modern’ pieces are confronted in the Pavilion with the work of artists linked to Colourism: Jan Cybis, Artur Nacht-Samborski, Piotr Potworowski and Eugeniusz Geppert, whose influence the young wanted to avoid. Colourists (or Kapists) most frequently addressed the subjects of still life, landscape and nudes. In abandoning the illusion of depth, by rejecting the outline and modelling, they simply ‘built a picture using colour’. For the generation starting out in the aftermath of the war their approach smacked unbearably of the Academia and was not progressive enough, and yet the influence of Kapism is clearly visible in the art of Socialist Realism, in the trend of Lyrical Abstraction and Informal Art, as well as in contemporary abstract painting.

The next part of the exhibition shows works of art created after 1949, when the doctrine of Socialist Realism was officially implemented in Poland. It imposed a schematic composition, a programmed optimism, and above all, the canon of obligatory themes (portraits of ‘Heroes of Socialist Labour’, working people, national leaders, industrial landscape of the country in the process of development, etc.).

Due to the political reasons many artists withdrew at that time from public life, while others tried to adapt to the new reality and the official aesthetics. One of the best known ‘socrealistic’ paintings is the picture Podaj cegłę [Pass a brick] (1950) by Aleksander Kobzdej. The artist using traditional painting techniques immortalised the so-called ‘brick-laying troika’, hard at work building a new house. Kobzdej’s picture became the symbol of creating the new Polish state, the People’s Republic, and its propaganda-style title became a contemporary catchphrase.

The painting came to the collection of the National Museum in Wrocław in 1968 from the chapel of the Zamoyski palace in Kozłówka. During the 1960s it was used for storing unwanted artefacts. Since 1994 the old palace carriage house has become the Gallery of the Art of Socialist Realism.

Another part of the exhibition pays tribute to the memory of the terrors of the war and the crimes of the Holocaust, painfully present in both the art of those who witnessed them, like Waldemar Cwenarski, Alina Szapocznikow, Andrzej Wróblewski, Marek Oberländer, Józef Szajna, Władysław Hasior, and in the mindset of the next generations of artists – Mirosław Bałka and Krzysztof M. Bednarski. The artists who were touched by the trauma of war frequently used motifs of a deformed human shape, apocalyptic landscape of destruction and the universal tragedy of human existence.

The extraordinary formula of painting, characteristic for the tragically deceased Andrzej Wróblewski – one of the most inspiring Polish artists of the 20th century, is shown in Cień Hiroszimy [Shadow of Hiroshima](1957), a picture based on the synthesis of Realism and Abstraction with the use of a well-defined contour and flat blocks of colour.

The latter part of the 1950s, following the relative political liberalization of the regime in Poland called the ‘thaw’, brought an outburst of a whole range of abstract painting styles: lyrical, geometrical and Informal Art. New personalities appeared on the scene, soon to become both the classics of post-war Polish painting and the masters for the next generations of artists. One should mention Tadeusz Brzozowski and Jerzy Tchórzewski, who represented an allusive and at the same time more literary trend, as well as the paintings devoid of subject matter by Alfred Lenica, a creator of experimental expressive works of art, and Stefan Gierowski with his monumental contemplative compositions.

Tadeusz Brzozowski used anonymous metaphorical figuration resembling organic abstraction, creating one of a kind, absolutely unique ‘alchemy’ of colour. He also gave his works grotesque and ambiguous titles made up from old and obsolete words. For example, Zycbad, 1969, comes from German ‘Sitzbad’, meaning a metal bath with a seat and a backrest, as well as such bathing style and … participating in a lengthy meeting.

Maria Jarema accomplished a completely different and extremely original style combining the ideas of the pre-war Avant-garde with abstraction and metaphorical painting. She explored the relations between mass, space, movement and colour, her filled with rhythm compositions give an impression of exceptional lightness, luminescence and freshness like Kompozycja (1955), in which the artist combined monotype printing and painting with distemper.

The artists who used metaphorical thinking in their paintings were also close to the poetics of surrealism and magical realism (Kazimierz Mikulski, Erna Rosenstein, Zbigniew Makowski), and connected the poetics of dream with lyrical abstraction (Stanisław Fijałkowski). Geometrical order, recalling the forms already existing in nature, appears in the work of art by, among others, Adam Marczyński, Alfons Mazurkiewicz and Józef Hałas.

The search inspired by geometrical abstraction features in the paintings by the most senior representative of Polish Constructivism and the Avant-garde master, Henryk Stażewski. At the end of the 1950s he introduced into his technique a relief – structure which remains somewhere between painting and sculpture. His studies of the interdependences of ‘relations, proportions and constructions’ were focused on the concept of space, light and movement, as in his Relief 5 (1965).

Henryk Stażewski, together with Władysław Strzemiński, was the co-creator of the International Collection of Modern Art in the Museum of Art in Łódź. Just like Maria Jarema, he was an important voice in artistic circles, and the flat-cum-studio which he shared from 1970 with Edward Krasiński, became an important place for open meetings and discussions for people connected with the arts. Nowadays it houses the Institute of Avant-garde run by the Foundation of Gallery Foksal.

The next stage of the revolution in 20th century art was the trend, which emerged in France and in the US, of Informal Art (French ‘informel’, i.e. formless art’). Formless abstraction rejected the old rules of composition in favour of a spontaneous brushstroke reflecting inner life and emotional states. Its main characteristic was the fascination with the material itself, the physical properties of paint and the substance of a picture. This trend is represented in our exposition by the work of its Polish forerunners, Tadeusz Kantor and Alfred Lenica, also Rajmund Ziemski and Stefan Gierowski.

Many artists followed their intuition, searching outside the mainstream and consistently shaping their recognizably private universe. Among them were: the creator of unusual dream-like linotypes, Józef Gielniak, and Jerzy Nowosielski, a painter who invented his individual style rooted in the tradition of orthodox icons, based on the synthesis of form and the unique combination of figurative and abstract art as in the painting Nude at the window (1965). Jan Lebenstein also had his very own style, a form of figurative painting based on simplified modelling and deformation, steeped in existential fears. His compositions, usually monochromatic and only sometimes livened-up with the use of strong blocks of colour, are filled with sophisticated structural effects.

Another important influence in Polish art came from structure painting, a trend intensively developed between the 1950s and 1960s under the influence of Informal Art whose essence was based on the expressiveness of matter and exploiting its properties. In its many examples the painter’s material was mixed with wax, metal, wood and even with objects of everyday use. The picture assumed the form of an ‘object’. The boundaries between painting, sculpture, artistic and non-artistic objects were deliberately blurred. In the Pavilion this trend is represented by, among others, a spatial Composition (1969) by Jadwiga Maziarska, one of its early exponents also on the European scale, who used an interesting combination of paint and stearin.

Structure painting went beyond the traditional plane of a two-dimensional picture. Artists began to elevate to the rank of art common everyday objects, referred to as ‘ready mades’. Those things, devoid of their primary function, appeared in assamblages – works of art made up from ‘non-artistic’ objects, the things found anywhere, combined with those typically artistic. In 1962 Tadeusz Kantor reached for items in everyday use and incorporated them into the space of his canvases, thus attempting to integrate art with life and at the same time rescuing those used-up objects from the ‘lower ranks of reality’. The exhibition presents the so-called emballages (‘wrapped-up’ pictures) whose most important elements are such commonplace things like umbrellas or paper bags.

Tadeusz Kantor was one of the most charismatic personalities in Polish art in the second half of the 20th century. He was active both in fine arts and on the stage. In his theatre, Cricot 2, Kantor showed performances with his own scenography, initially based on the texts by Witkacy, and later also his own like The Dead Class (1975), Wielopole, Wielopole (1979) and Today Is My Birthday (1990) which later became world-famous.

Unique examples of ‘assamblage’ came from the incredibly imaginative Władysław Hasior, who out of retrieved common debris like toys, mirrors, cutlery, photographs and scrap metal composed symbolic, metaphorical objects tinged with a perverse sense of humour. In his references to tradition, history, art, religion, national martyrdom and literary themes, the artist used the grotesque and kitsch to assist in a tender and thoughtful description of the reality.

In his Icarus (1962) Władysław Hasior made an ironic reference to the Greek myth of Icarus, also using a fragment of the reproduction of Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (1483–1485).

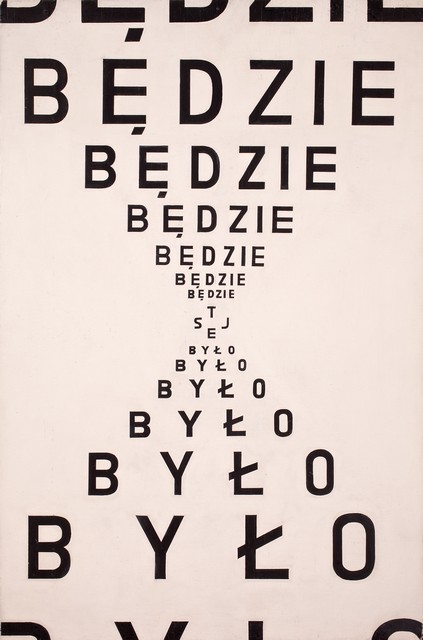

In the 1960s the art world turned its interest towards the creative process itself. Conceptualism meant that even an idea itself soon became art. The artists associated with the famous Mona Lisa Gallery in Wrocław: Jan Chwałczyk, Wanda Gołkowska, Jerzy Rosołowicz and Zdzisław Jurkiewicz, whose work can be seen in the courtyard of the Four Domes Pavilion, linked art with science and technology, materialization of light, concepts of continuity and infinity. Visualization of language and its analysis became the subject of Concrete poems by the eminent poet Stanisław Dróżdż, the passing of time was registered by Roman Opałka, and Ryszard Winiarski depicted statistical distributions which were the images of the throws of dice. Edward Krasiński in his Interventions (starting from 1967) marked space with a continuous line by placing a sticky blue tape (‘blue scotch’) which became his trademark, at the steady height of 130cm.

The first great demonstration of conceptual art in Poland was the artistic event Sympozjum Plastyczne Wrocław ’70, widely acknowledged as a breakthrough point in the history of Polish avant-garde art. At the same time, Zbigniew Gostomski created his work It All Starts in Wrocław (1970).

The 1970s, the time of a developing phenomenon of counter-culture, involved the following artists: Eugeniusz Get-Stankiewicz, Jan Jaromir Aleksiun, Jan Sawka, Jan Dobkowski, Jurry Zieliński, Ewa Kuryluk, Edward Dwurnik, Ryszard Zamorski. Their work, often inspired by pop-art, is an expression of contesting the popular custom and culture. This art is characterised by its concise message, irony, rejection of the official propaganda and hypocrisy in social and political life.

The unique, largest in Poland collection of art by Magdalena Abakanowicz, a truly exceptional sculptress, occupies a special place in this exhibition. In the early 1960s the artist revolutionised the approach to cloth by making completely innovative ‘soft sculptures’ using dyed sisal, which nowadays are universally known as ‘Abakans’. The organic forms, suspended in the space stretching under the north dome of the Pavilion, surprise with their expression, scale and texture.

The open-air installations by Abakanowicz can be found in many locations all over the world, from the US, France to Lithuania. In front of the entrance to the Four Domes Pavilion visitors can admire her two monumental pieces (Birds, 2007–2008).

The next part of the exposition presents the work of the distinguished sculptress Alina Szapocznikow, the first exponents of Polish feminist art Maria Pinińska-Bereś and Natalia Lach-Lachowicz, and the intermedia artists Izabella Gustowska, Katarzyna Kozyra and Joanna Rajkowska. These artists, while seeking new forms of expression, examine aspects of carnality and eroticism, the place of women in society, as well as the problems of intimacy and the passing of time.

Alina Szapocznikow has an exceptional place in the collection; by experimenting with new materials like polyurethane and vinyl she created works of art with extraordinary force of expression. Her sculptures, which remain on the verges of figurative Monument for the Burnt City], 1954) and abstract Layered Tumours II (1970–1971), form a particular apotheosis of life and all its hues – from subtle erotic enchantment with the beauty of youth, to the attempts at preserving moments in time, memories of the body, familiarity with illness and with the fear of death.

In 1969 Szapocznikow was diagnosed with cancer. The experience of illness found an extremely moving expression in her art when the artists used the casts of her own body to create sculptures.

Another part of the exposition is dedicated to the art of the 1970s and 1980s when the majority of artists boycotted the official cultural scene. Those who were connected with the unofficial alternative culture organized exhibitions in churches and in private homes. A table ‘kneeling’ in prayer, the installation by Jerzy Kalina Angelus Table (kneeling table) (1984), a huddled figure in a Cage (1981) by Magdalena Abakanowicz, fencing and barbed wire made into Net (1989) by Włodzimierz Borowski, are the metaphors of enslavement. A raw, simplified form resembling a totem sculpture Political Shrine (1976) by Jerzy Bereś is a protest against the oppressive reality, ironically depicted in People’s Madness (1981) by Edward Dwurnik.

At the same time expressive, critical young art, such as that of Nowi Dzicy [the New Savages] and the so-called trans-avant-garde, was also an expression of rebellion against the stark reality of the PRL. The artists, using the grotesque, ridiculed the absurd world which surrounded them, applied simplified composition rules and strong, sharply contrasting colours. The exposition includes work of the artists from the Warsaw Gruppa (Jarosław Modzelewski, Marek Sobczyk), and also local ones: Zdzisław Nitka, Eugeniusz Minciel and Krzysztof Skarbek. A special phenomenon of that time was the activity of the Luxus group based in Wrocław, which in reference to the Western mass culture reached out to the tradition of Dada collage, made use of pastiche and irony, as well as the readily applied stencil, often signing off their work just with the group name.

In the cycle of paintings Guards (1994) – coloured portraits of large cats – the stencil technique was used to make a mocking reference to the pop-art multiplications made by Andy Warhol.

Works of artists who are influential in today’s image of Polish art can be seen in the last room. Among them, Leon Tarasewicz whose art close to abstraction originates from his fascination with nature, which is also a source of the whole wealth of nuances of colour and structure, Lech Twardowski who combines the expressive brushstroke and energetic splashes of colour with geometrical order of large spatial forms. Piotr Janas and Jakub Julian Ziółkowski lead an interesting dialogue with the past, mixing what is contemporary with the tradition of painting matter, gesture and the poetics of surrealism. Finally, there are works by Paweł Althamer such as the expressive sculpture Bärbel, created in 2011 as part of the Almech project realized at the Deutsche Guggenheim gallery in Berlin. The artist made casts from the faces of the gallery staff and some of its visitors, and afterwards set them onto lace-like polyethylene bodies.

From the last room one can progress to the one dedicated to temporary exhibitions. The collection is steadily expanding, and includes work by renowned masters as well as up and coming young artists, just as the exposition itself in the Four Domes Pavilion Museum of Contemporary Art.